Welcome back.

I swear these shared stories are getting better and better with each volume we publish. This ocean tale has so many twists and turns in it that you won’t be able to stop reading until the end. And it’s all down to the six brave Playground Visitors who agreed to put pen to paper with me.

I highly recommend reading each author’s content, as you won’t be disappointed.

As always, if you feel like you can spin a good tale around our CAMPFIRE, don’t hesitate to join the next volume coming soon.

Ok, let’s get to the story.

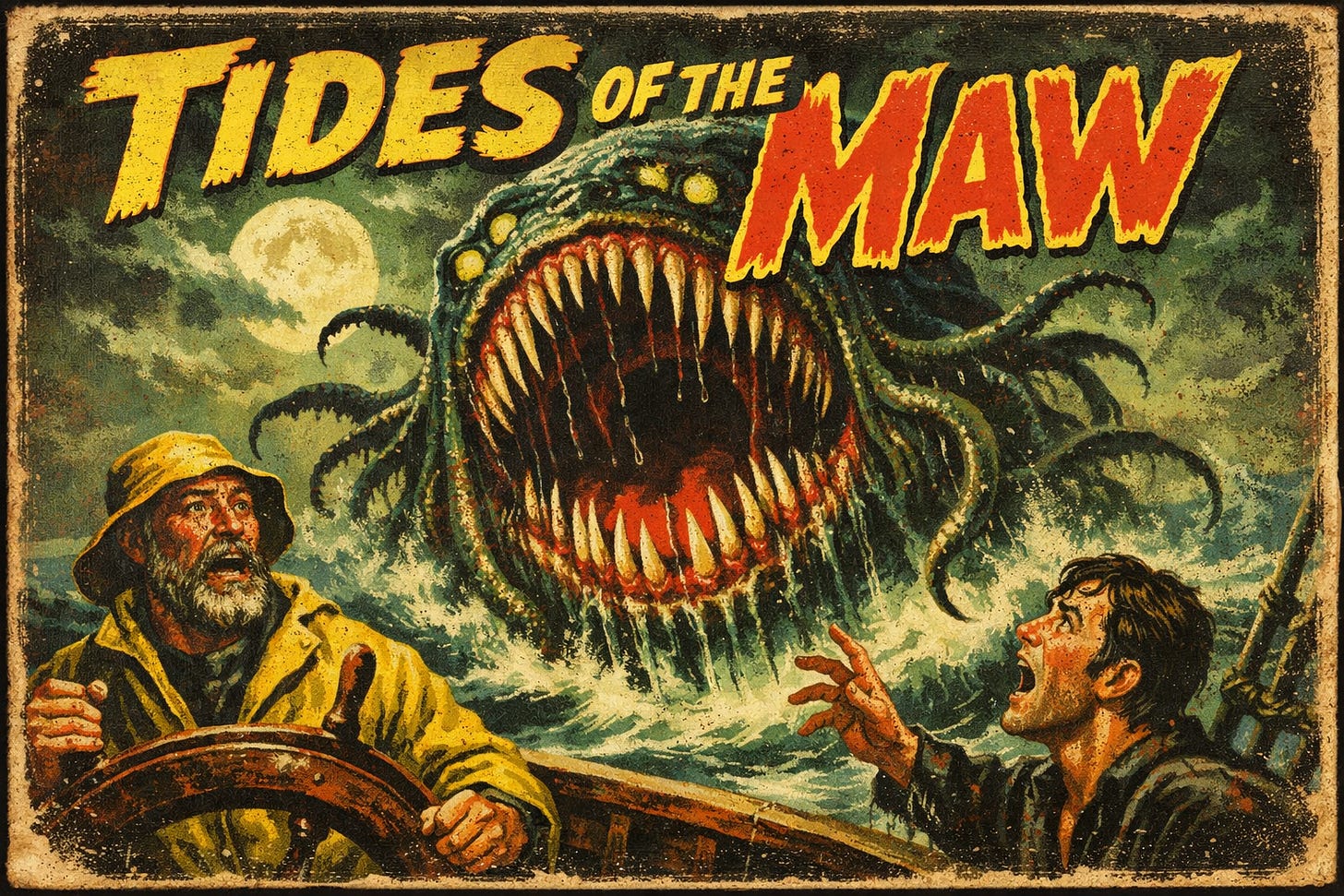

The Sea Maw’s Tide.

To those unlucky enough to read these pages, I pray God protect your soul. A fate worse than death closes around me, but not before I recount the island’s dark events on these pages. But the story does not start with me. No, his name was Stewart Harding, formerly a seaman aboard the merchant vessel Espion. His vessel was not thirty miles from the island when he retired to his bunk. He told me the sea looked calm as glass then, but by the setting of the sun, they were rocked by unnatural waves.

The vessel broke within an hour, and he was thrown overboard. He swore in that moment, a low roar erupted from the black waters. When next he woke, he found myself washed up upon the wastes of Devil’s Bay. Never was a desolation more aptly named. Thankful to be alive, he moved to stand, but a new pain in his shoulder almost took away his breath.

How were we all to know the nightmare had only just begun?

I was finishing my second Wight Gold and about to open my third when I overheard the stranger talking and introduced myself to him from the woodland path just off the Bay. I told him my name was Richard Branson. I gave him a painkiller and began addressing his yarn. I said that the islanders here don’t say its true name. Not if they value sleep, or the thin membrane separating a man’s sanity from the deep.

But I told Stewart that since he survived a shipwreck tonight, he ought to get some rum into him. And while it did its thing, I would do some recounting of my own. I noticed the wound on his shoulder, warning him immediately that dark poison was now working through his body. I told him that I reckoned the thing he’d encountered had already marked him, what’s whispered in Veilpoint when the shutters are latched, and the tide is breathing low.

Some call it the Veilpoint Wraith. Others, older islanders who remember what their grandparents muttered in patois around guttering lamps, call it La Gueule-de-Mer, the Sea Maw. A creature not born but ‘remembered’ by the ocean, as though the water itself had nightmares and coughed it up.

Stewart said his ship, the Espion, didn’t sink. It ‘came apart’, as if something pried it open like a crab shell. That fits. Boats here are unmade, quietly, efficiently, as though by some terrible artisan of hunger. Picture something vast but never fully seen. No one has glimpsed the whole of it. Some see a serpentine ridge breaking the surface, not scales, but a hide like wet basalt, pitted with scars that shine faintly blue.

Others speak of tendrils, thin as anchor lines yet strong enough to drag a cutter sideways through a gale. But they all agree on one thing, it moves without sound. The creature rises as if displacing light rather than water. Shadows float before it. Then everything is swallowed.

As for the missing members of Stewart’s crew? If they were lucky, they died before the water touched them. The Maw likes to pull men off ships one by one. Not drowning them, no, no, taking them. Sometimes fishermen find bodies washed ashore weeks later, faces contorted as though they died mid-scream. Though, their lungs contain no water.

Stewart told me that last night was calm until the waves suddenly heaved like the whole bay exhaled. That’s exactly how it begins. First, the stillness. Then the upward rush, as though something is rising beneath. No roar. No splash. Just the soft, obscene groan of wood forced apart by patient strength. If any piece of the Espion remained floating at dawn, it was a courtesy.

Boats vanish out there, I said. And I told him that every few years, some poor bastard like him crawls back to tell the tale. Hands shaking, eyes haunted, smelling of salt water and fear. You didn’t just lose your ship, Stewart, I told him. You survived its choosing.

And around here, that’s the worst omen of all. Because once it notices a man, it tends to notice him again. And if you believe none of this, ask yourself why every local refuses to fish Devil’s Bay after dark. Because we know what waits beneath. And now, so do you.

Later that night.

I laid Stewart on a crude table made of driftwood and shipwreck scraps. I fetched a bucket carved from some ancient timber dark as pitch. “I’m nothing but an old swallywog,” I told him. “I go by Hensworth, associate of Branson.”

“Ah,” he said, “Tell me, Hensworth, you old swallywog, have you heard of the sea monster?”

“Once,” I said, “from a madman. Lie back,” I told him. “And quit jabbering. There’s poison welling in your wounds.”

“The Sea Monster, you old fool,” Stewart grunted as I sliced just enough of his wounds to let his thick, near-black blood funnel into the bucket, as Branson had commanded. His body was already changing. “Green eyes that glow? How did your madman describe him? How did he describe it?”

I said, wiping the blood-letting blade on a rag stiff with the blood of others. “The madman claimed the creature had no shape of its own—only the shape a guilty man expects. Some swore it bore horns; others that its hide was smooth as slate and cold as a magistrate’s stare.”

Stewart gripped the table. “A magistrate’s stare? You islanders turn everything into a sermon.”

“Aye,” I said, “aye.”

Stewart’s blood thudded into the bucket, slow as a grave clock. “The beast hunts by the scent of dread,” I told him. “If it has risen tonight, I suppose it’ll be heading north to Veilpoint, where some dark groups of men summon it every year. You and the creature seem to be heading in the same direction….”

He tried to laugh. “You’ve a poet’s tongue for a swallywog in a wolf’s hut, Hensworth. But your madman knows not of my sea monster,” Stewart said. “The thing I saw had no horns or hide. It rose from the deep like a question God never meant to be answered. Longer than any hull, moving as if weight were nothing. Its skin shifted like tar—smooth, then crawling with shapes I pray weren’t eyes. It breathed. The sea swelled as though the whole ocean were its chest. And when it turned, it noticed me, like a man spotting a splinter he means to pluck. And those green lights—they weren’t eyes. They were wounds. Glowing wounds.”

He shuddered.

“That is what I saw.”

No sooner had he spoken when the hut’s door flew open, and the Island’s hag walked in.

From the back of the sooty dark room, the hag’s voice cut the air like a dull saw on a sheet of metal, “Let him go, Hensworth. . He won’t last long enough to reach the road to the village.” She shuffled into the dim light, hungrily eyeing the bucket of blood. “This is what we need. We are protected now.”

I reached for the bucket, but the hag was quicker than I was. She was already retreating into the shadows, her two hands clutching the handle of the bucket.

I hated her with every ounce of my soul. She let Minerva die. My Minerva. A sacrifice. Let’s see how powerful she really is, I thought. That vicious woman believed she could harness the Sea Maw’s cursed venom. Let’s see if it protects her precious grandson, Victor. Let’s see if it protects anyone in Veilpoint. But I had to act quickly; Steward’s exsanguinated body would only incite the beast’s appetite.

Pulling the blood-stiffened rag from my pocket, I started to run, marking the leaves, the grass, the tree bark. Anything that would call the creature to the other cultists in Veilpoint and to Victor.

Veilport was something like a funnel. A thin access road on the north side fed to the towns beyond the Bell Mountain range, and back to Veilport going the other way. Here, Veilport was a fat stripe of shops and huts with the broad stone stripe of the port of Devils Bay and the waterfront. Continuing south, the town became thinner again and more or less dead-ended. The roads here were dirt, leading to properties no one in their right mind would visit. The disciples of the Sea Monster, led by the hag, gathered here to...worship. Not sure what to call it.

It was too late to save Stewart when I caught up to him, but Hensworth was keeping his end of our deal, using Stewart’s blood to lure the creature to the town. I knew a rough idea of the legend. The Sea Monster was part siren, part sucubus. It lured the Espion to haul its crew into the water. (They’d gone off route a few miles from the intended destination, I found out later.) Once on board, it wrecked the ship, and...infected a few of the crew. The Sea Monster couldn’t really crawl onto Devil’s Bay, but it could do a dual attack of infecting a few people, whispering a siren song that goes straight to the heads of people with dark leanings. The first-infected infect the believers who only know of the creature by the song, when enough of them gather to make a sort of offspring of the creature.

We’d see about that.

The legend I had was enough to make a plan. Stewart wasn’t going to help as a man, but his scattered body parts were a better magnet to bring the disciples together than the blood Hensworth was carrying. I would start at the north end of Veilport, luring the creatures with Stewart’s arm and shoulder stained with a good amount of black goo on them. Then the rest of his parts would make a handy trail, taking the creatures back to the south end, to the woods, where I would be waiting with Stewart’s head by my boots. A torch in my hand would make me easily seen, but hiding tar all around the dark plain. They’d be guided by the scent of the black goo, not noticing anything else, with the hag leading them. When they got close, the torch and the tar would finish them, and I’d be known as Branson the liberator. The man who freed Veilport from the course of the creature.

The bucket reeked, and I was covered in it.

Not regular blood that dries sharp and metallic, but the slick, tarry stink of something becoming wretched. It clung to the air like humidity before a storm, sweet yet menacing. The smell carried weight. Rot mixed with brine. The kind of rot time carves into things left for dead. The scent that drifts up from shipwrecks long before the missing are found.

I moved quickly through the scrub, a blood and tar-soaked rag in my hand, marking the trees. Bark. Leaves. Stones. Each swipe deliberate, purposeful. Kill them all. Kill the beast. Kill them all. A wet, glistening smear pointing north toward Veilpoint. A perfect trail of tears I would set ablaze. I would end this nightmare once and for all.

“Branson?” Her voice cracked like wood splitting in a fire. “What’s happening?”

I spun. Moonlight struck her face, then mine. My eyes were fearless, not calm but resigned. The ruthless stare of a man who has already made peace with dying.

“Go back,” I said flatly. “This isn’t for you.”

“The hell it isn’t.” She stepped closer, driving her palm into her ribs. The gash beneath her shirt smoldered faintly, pulsing like a second heartbeat. Not human. Too rhythmic to be random. “This’s a trail. You and Hensworth are calling it here.”

My gaze, now firmly fixated on the glow seeping through her fingers. I didn’t need the moonlight to see it.

“You’re marked,” I said with a brief, pitying look.

“You think I don’t already know that?” she snapped. “Happened three nights ago when I dove too deep into the sea. The hag’s supposed to have a cure.”

I laughed, a bitter and broken exhale that felt like something splintered inside me. “The hag cures no one. All she does is collect and study. Let the poison simmer until our bodies bend. Then she feeds victims to her Sea Maw when they’re soft enough.”

Her face dropped. “So why’re you leading it straight to town?”

“Not to town.” I dragged the rag across another trunk. The blackened blood glistened like oil. “To the disciples. To the cult in the north field. To Victor and the hag and all those fools who think they can harness its power. Let them face what they’ve summoned.”

A new wind whipped her hair across her face. It carried a low groan from the bay, like timber breaking underwater. Slow. Inevitable. It wasn’t a sound. It was pressure. Behind the eyes. In the teeth. And it was rising.

“You don’t understand,” she said, voice thin. “The Sea Maw doesn’t just hunt the marked. It hunts everything in its path. There’s families in Veilpoint. Children. People with no part in that hag’s madness.”

“Then they should’ve stopped her years ago,” I said. “Just like they should’ve stopped her when she took Minerva and let the creature drag my love into the water and twist her into a serpentine ridge of horrors. Every damn person in Veilpoint who stayed silent is complicit.”

My voice broke on her name. The grief beneath the rage pulsed like the poison in Keira’s wound.

“I’m sorry about Minerva,” she whispered.

“No.” I shook my head. “You’re not. But you will be.”

Another groan rolled out across the bay. Her wound throbbed in time with it, glowing hotter and brighter. For a moment, she looked ready to run straight into the water and let the dark take her.

“You feel it,” I said, quietly pleased. “The calling. The poison telling you the water’s the only place the pain’ll ever stop.”

She clenched her teeth. “I’m fighting it.”

“For now.” I stepped closer. “But I’ve seen what comes next. Fever. Luminescent flesh becoming tendrils. Then the calling. By dawn, your skin will thicken and split. Your bones’ll shift. And your eyes…” I swallowed hard. “Eyes begin to surface in places eyes shouldn’t never be. They don’t blink. Or sleep. They just watch.”

“Branson. Please stop,” she whispered.

“The hag won’t cure you,” I explained further. “She’ll watch you change, scribbling notes while each of your organs succumbs to its fate.”

“So what?” she barked. “You lure the Maw to devour the town, and I just become…” she stopped.

I reached into my coat and pulled out a tiny vial. The liquid inside wasn’t anything natural. It glimmered like a black opal in firelight and seemed to swallow the faint glow of the forest around us.

“This was rendered from a man named Stewart. The only piece that doesn’t regenerate. He washed ashore after another Maw tore into his ship.” I swirled it. “Mix it with the ashes of the taken. Ashes, the hag guards. Burn it with fire from a drowned man’s pyre. Only then does it become a cure.”

She choked on her breath.

“Every night since Minerva was taken, I’ve planned this,” I said. “I’ve watched that woman poison the island, sacrifice the people I loved, and call it protection.”

Below us, the water churned. Lightning flickered from bioluminescence threading the darkness. Something rose. Something immensely terrifying.

Multiple ridges broke the surface, horned and scarred. Entrails slid through crevices. Unblinking eyes dotted the thick, waxen hide.

“How many ridges have you seen?” she asked.

“Dozens,” I frowned. “Why?”

“Each one’s a person. The old islanders called it Kèt-aqan, the thing that devours itself to grow. Every soul it claims becomes part of it. Another ridge. Another eye. A collection of the damned.”

I stared at the mass rising from the water. Scars glowed faint blue.

“Minerva,” I breathed.

“Can you see her?” she whispered.

“There. That crescent scar. On the right.” A ridge rolled through the moonlight, and a faint silver crescent gleamed along its edge.

Her face tightened. “My grandmother used to say the victims stay conscious inside the Maw. Awake and aware. Trapped. Unable to speak. Unable to die.”

My chest ached. “I’ll burn Minerva free. I’ll burn all of them for free.”

She held my gaze.

The stench from the bucket rose thick. Stewart’s rotting blood clung to my clothes and hands.

“The vial’s yours,” I said, softening. “I don’t know if it’ll work on someone as far gone as you, but you’ll only get it if you help me.”

Her desperation flickered. I felt it like heat.

“We move now,” I pressed. “The creature’s already following my trail.”

At the fork, she sprinted toward Veilpoint, the venom in her veins pushing her onward. I dragged my blood and tar lure toward the cult’s field.

Behind us, the Maw bellowed again. This time, I heard voices inside the sound.

Hundreds.

Speaking together.

Calling the infected.

The bucket vibrated in my grip. Black liquid rippled toward the sound and seemed to answer the siren’s call. The ground trembled under my boots as something far older than either of us began to rise.

One month later.

Field Notes: X O - III - The Rise of King Richard

“In retrospect, there was no stopping it. I was a fool to try. The island overflows with howling scaled banshees. The Hag, her family, everyone I have ever known, loved, or, more importantly, hated, have succumbed to the will of that damn beast. I hear them shrieking out there, chattering, howling into the night. Still, I am the only man left, and that makes me King.

King Hensworth, no, he is dead now, too. I am King Richard Branson.

The life of a King is not an easy one. Not here, anyways. Supplies are running low, and there’s little chance of survival if I go out there and try to gather more. With lack of humanity, real humanity, there is no civic maintenance taking place either. No development. It was a jungle out there, now it really is a jungle out there, and it is overflowing with apex predators who exist solely to strip me of everything I am and make me one of them.

My stomach hurts, oh Lord, does my stomach hurt.

If I have to eat another bowl of Shrub Bounder stew, I think I’d rather lower myself to shambling around the island devouring anything with a pulse just like those damned thralls. Luckily, I have plenty of Wight Gold. Or, had plenty. I couldn’t do any of this without it, or my Minerva. Over the past few weeks, Minerva has been talking to me from the sea, comforting me. She’s tried to convince me to leave this place, head out, and find some form of humanity beyond this island.

Until now, I have refused, politely, of course. Here we are, King and Queen of all the living. Why would I want to leave?

But, apparently, tonight is the night I must confront the Wraith.

Night swimming with the Sea Maw.

I will do it for her; she has always asked me so sweetly after all.”

Naked, a mad Richard Branson looked over the black waters. The whole world behind him was screaming with unearthly massacre. Drunk, he swayed on the balls of his feet, listening to a lullaby that was music to nobody’s ears but his. First one step, and then another, as his feet breached the water’s surface. A ripple, a low growl, and just like that, Branson was front crawling through the cosmos.

To escape the eventuality of the island meant facing the certainty of an encounter with what waited beneath, and yet his arms cut through the sea as though the ocean had taken pity on him and parted itself for ease of passage.

He swam for what felt like hours. Hours without breathlessness. Hours without the lactic acid burning in his limbs. The liquor left his blood, and yet the exhaustion still never came. The water carried him like an understanding mother finally letting her wayward son come home. The screams of Veilpoint faded into the distance until they sounded like stars cracking against one another in the beyond.

Then? Light.

Two dozen at first, glittering faintly on the horizon like a string of coastal windows, a seaside town nestled in safety. He laughed, or tried to.

The sound came out wrong, monstrous, swallowed whole by the ocean the moment it left his throat.

The lights beckoned him.

He swam harder, though he still did not tire, until eventually the little pinpricks began to vanish one by one. Blotted out, as though the curtains were being drawn. Or swallowed. Or smothered.

Soon, only two lights remained. Dazzling. Steady. Perfectly symmetrical.

“Lighthouses,” he whispered to no one. “A twin set guiding me in.”

He kept swimming.

The water below him grew warmer, thicker, syrup-dark. Like sludge or slime. Goo. It curled around his wrists and ankles like eager fingers. Curious fingers. And the twin lights grew brighter. Unnaturally bright. No lighthouse glowed like that. No human flame held such ancient power.

He swam closer.

The lights blinked.

He froze. Not from cold. From understanding.

The lights weren’t on the horizon.

They were above him. High. Higher. Higher still.

He lifted his head out of the water to look up, and every piece of his mind recoiled, then cracked, then crawled back to look again. The two lights were not lighthouses. They were not windows. Not fires. Not lanterns.

They were eyes.

Colossal eyes set in a shape that was not a shape, a form that refused form, a silhouette too large to belong to sea or sky or memory. It rose like a mountain breaking the surface of the world, yet he felt no splash, no wave, no shift in the tide. It simply was, waiting for him as though eternity had arranged his arrival. The lullaby in his head grew louder.

Sweeter.

Older.

Minerva’s voice melted into something vast and indifferent, something that understood guilt better than any god. The stars wheeled above him in patterns that had never existed, threads of impossible geometry stitching themselves through the air.

Branson could not swim anymore.

He could only drift toward the two blazing eyes watching him like a mother watches a cradle.

“The Maw.” He whispered, not in fear but in trembling recognition. And the Maw blinked again, slowly, its eyelids like continents sliding over creation. The water around him rose of its own will, lifting him toward the towering shape. A low roar, older than storms and seas, vibrated through his chest until his bones vibrated.

The cosmos bent.

The Wraith breathed.

And Richard Branson finally understood his beloved Mineva’s lullaby.

It was never meant to guide him home.

It was meant to guide him here.

Such good, terrible fun! A pleasure to write amongst you. Thank you, Wirrowac, for facilitating this spell of storytelling.

I wish my fellow scribes a joyous holiday season and the inspiration of the Gods to continue this God forsaken pursuit in 2026. Thank you to Wirrowac, for the invite, for his wit and imagination, and for his delight in creating this playground.