Hello, and welcome to my journey as a writer, both on SUBSTACK and beyond. Bedded within CAMPFIRE’s 4, a key event caught my attention, enough that I’m compelled to expand on the work as a whole.

Steward is murdered halfway through, after his blood was drained (with his carved-up body scattered in the fields to lure out evil cultists).

That may not seem like much on the surface, but for me, paradigm-shifting. Why? Because Protagonists aren’t supposed to die so unceremoniously. The notion has never even entered my head while writing my own stories. When I was preparing CAMPFIRES, I imagined Steward long decent across the island, mutating as he went. Well, thankfully, that version never happened. Steward died, and Branson carried the rest of the narrative. That subversion—challenging expectation rather than fulfilling it—is what ultimately made the story feel unique to me, and worth expanding.

Now hooked on the story, I’m currently building an outline, and today, I’m lifting the curtain just a tad in the hopes it may help you in whatever you’re writing about. First, I recommend reading the original story. My contribution comes first, and that’s what we’ll focus on today.

Outline 1

Chapter One- Scene beats

A prayer or warning, not pleading for belief but for forgiveness.

Then a shift to Steward aboard the Espion. Described as an unnatural calm sea. The ship doesn’t sink—it comes apart.

Steward wakes on the shore with pain in his shoulder. The land feels hostile but indifferent.

Not bad for a two-hundred-word introduction, and I noticed my opening part was doing what a lot of horror openings do well.

Atmospherically? It worked.

Structurally? Kind of fragile.

After extracting a basic outline from the story we’d told together (above), I realized something uncomfortable. In my part, I was telling the reader what the story was before things developed.

The biggest takeaway is in the above version, interpretation is already complete. Stewart knows what happened, and you’re told how to feel. Meaning was asserted, not discovered, and that’s not good for the reader.

Emergent Narrative Theory

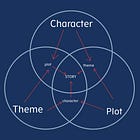

That’s where E.N.T. theory will step in and force me to be honest. ENT, in simple terms, is how I stop myself from mistaking gimmicks for meaning. It treats character, plot, and theme not as separate tracks, but as a holistic pressure system. Therefore, the story must emerge through meaning derived from decisions made under incomplete information.

ENT theory asks a blunt question at moments like this:

Who is experiencing pressure right now—and who is doing the interpreting?

Here is an updated outline after a lot of thinking.

Outline 2

CHAPTER 1 — Devil’s Cove: Shipwreck over calm seas.

Purpose:

Introduce a shipwrecked crew, ambiguity as to what happened, and the idea that survival itself is suspicious.

Key Beats:

Opening view of a desolate bay.

Steward, Hemsworth, and Bradly stand over half a corpse.

The corpse is not cleanly torn — it looks selected, incomplete.

The men argue over who it was:

Hemsworth wants an explanation. (Who was it?)

Bradly wants certainty. (What killed him?), mentioning the shipwreck above calm waves.

Steward is silent — The tide feels wrong. After a lifetime on the sea, the ocean has betrayed him. (Why did this happen to me?)

Bradly rationalizes that the ship must have hit a sunken reef. Hemsworth has his doubts, but before he talks, Steward keels over in pain. Steward’s shoulder wound is evident. He downplays it, and others accept this lie because they need to survive (they need to be mobile).

The group grudgingly decides to follow a feint path inland, away from the sea, and seek treatment for Stewards’ wounds.

In this update, Stewart isn’t alone. He stands on a desolate coastline with two others staring down at what remains of a crewman, with no shared understanding of their situation. Doubt, mistrust, and conflict begin immediately. For chapter one, a difference of opinion between friends is all that’s needed. Enough to seed future fractures.

We also experience Devil’s Cove through Stewart’s eyes, which allows the environment to remain subjective rather than a catalogue of detailed, objective details. To support the opening atmosphere and Steward’s character more, I want the sea to seem like a betrayal to him. I imagined the sailor spending his life trusting the ocean, riding it, surviving by it. Then, this happens.

A shipwreck on calm waters makes no sense to him.

Rationalizing comes later in the story, where the sea monster will start to make an appearance. Chapter one introduces a personal rupture, and a physical one comes from the pain in his shoulder, which they all choose to ignore.

What I want to show you—

This new opening resists explanation. Meaning isn’t delivered; it’s pressured into existence by disagreement, pain, and incomplete information. Which I hope hooks readers into the story. The environment doesn’t announce itself as hostile. It simply feels wrong — because Steward feels wrong within himself. What matters in my work is not what the reader is told to fear, but what they begin to sense before they understand why.

Thank you for reading. Next week I’ll continue with my story outline.

Will we ever jump into sci-fi ideas?